A new breed of cyberattacks is surfacing — and they’re not just more frequent; they’re smarter and perilous. Beneath the surface, tactics are mutating fast, almost as if someone, or some network, is pulling strings deeper than we’re being told. Take “fast flux.” On paper, it sounds technical and nerdy- another DNS trick in a hacker’s handbook. But the implications? Far murkier.

Here’s what’s happening: cybercriminals, often backed (if not outright employed) by nation-state actors, are using this method to constantly change the DNS records of a single domain. That means the actual location of a malicious server can shift faster than most tracking tools can follow. One moment it’s pinging from Taiwan; seconds later, it’s bouncing off Estonia or tucked into a basement in Dubai.

Something’s Shifting in the Shadows of Cyberspace.

Publicly, agencies in the U.S., Australia, Canada, and New Zealand have issued coordinated advisories — an unusual move in itself. Officials are cautioning that these networks rely on more than code. Devices are being hijacked, yes, but that’s just step one. The malware triggered through such attacks are programmed to “call home” – a chilling phrase if you think about it. These tools aren’t just running automated scripts; they’re engaging in digital correspondence, waiting for further instructions from their unknown handlers.

What kind of actors are orchestrating this level of complexity? The official language points to “advanced persistent threats,” a sanitized term that often translates to “state-sponsored” or worse, state-tolerated. Which states, exactly, are a bit of an open secret? Off the record, intelligence circles hint at some familiar names.

There’s something else that’s difficult to ignore — the uncanny timing. Just as global tensions rise, cyber infrastructures grow more fragile. Systems that millions rely on are being probed, mapped, and quietly manipulated. It begs the question: are these just random attacks for profit, or are we witnessing digital groundwork being laid for something… larger?

The latest instances of it hint what we’re seeing is a dry run. Quiet invasions. Test environments. Malware that doesn’t just disable but listens, learns, waits. And perhaps most unsettling: it’s already inside systems we assume are secure.

Whether it’s organized crime evolving into cyber cartels or a silent cyber cold war escalating behind our screens, one thing’s clear — the battlefront has moved, and the battlefield is everywhere.

Read More: Why Small Businesses Are The New Bullseye For The Threat Actors?

The Technique- Detailed

It starts with a website. Harmless looking. Could be a login page. A form. A download link. Except, underneath the HTML and scripts, something’s alive, shifting, darting, disappearing. In the world of cybersecurity, these are the phantoms: malicious domains powered by a stealthy, near-impossible-to-pin-down technique called Fast Flux. What appears benign on the surface often hides something far more sinister beneath, and law enforcement isn’t just chasing ghosts—they’re chasing ghosts that vanish every five minutes.

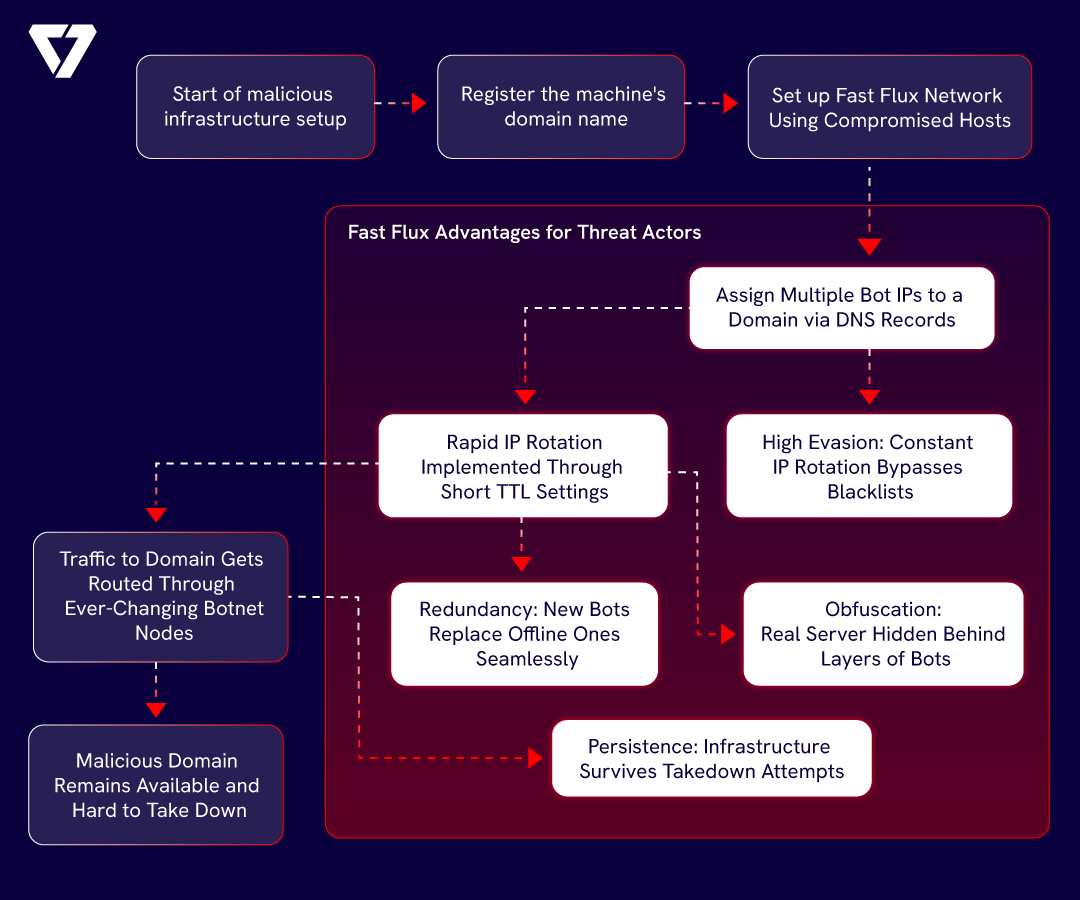

By rapidly rotating the IP addresses linked to a domain name, attackers create a dynamic infrastructure that defies traditional security measures like DNS filtering or IP blacklisting.

But it doesn’t stop there. Fast Flux networks often employ botnets—vast armies of compromised devices scattered across the globe—to act as proxies, routing traffic and shielding the real server from prying eyes. This decentralized setup ensures resilience; even if one node is taken down, the operation continues uninterrupted.

Here is how Fast Flux Works

The Deceptive Dance of IPs

Fast Flux is not just a tactic. It’s infrastructure — the spine of modern cybercriminal operations. In its essence, it’s a method for rapidly rotating the IP addresses associated with a domain name. A single domain might resolve to dozens, even hundreds, of IPs over a short period. These aren’t just randomly scattered servers either. They’re part of botnets — infected devices turned into unwilling relay stations, masking the real location of command-and-control centers and malware delivery nodes.

Think of it like a shell game. Except, the table’s on fire, the dealer’s wearing gloves, and the ball keeps changing shape.

Botnets: The Digital Mercenaries

Fast Flux leans heavily on botnets — vast swarms of compromised machines. Each of these acts as a proxy, a digital smoke grenade. Traffic bounces between them, rerouting and rerouting until even the most advanced firewall is out of breath trying to follow. It’s like trying to listen to a single voice in a room full of ventriloquists.

These networks, controlled by ransomware groups like Hive, Nefilim, the infamous GandCrab, and various others, have weaponized the technique to such a degree that takedowns have become laughably temporary. And the newer double flux method? It rotates both IPs and DNS name servers — think of it as hiding the hideout inside another moving hideout.

Read More: Why Every Business Needs An Incident Response Plan

Fast Flux in Action: Beyond the Buzzwords

Fast flux isn’t just about technical wizardry—it’s a toolset for persistent, high-impact operations. These techniques fuel a spectrum of malicious activities, including:

- Phishing and Credential Harvesting: Fast Flux keeps phishing pages alive even after being reported. The domain stays, but the IP changes, like a hydra regenerating heads.

- C2 Servers: Malware calls home – but the home is a decoy. And then another. And another.

- Data Exfiltration: As gigabytes of sensitive data are smuggled out, defenders are chasing ghosts across continents.

- Ransomware Delivery: Obfuscated payloads are hosted on constantly shifting IPs, defeating traditional blacklists.

It’s no exaggeration to say that a script blocking suspicious IPs can be swapped in a span of a few minutes. Protective DNS services and even machine learning models, trained on yesterday’s data, often falter in the face of such agility.

The Layers Beneath the Layers

We’re now seeing complex layers like domain generation algorithms (DGAs), bulletproof hosting providers, traffic tunneling, and living-off-the-land techniques. In some cases, attackers even spoofed IP ranges from Fortune 100 companies. This isn’t just evasion. It’s deception refined to an art form.

But to truly grasp the sophistication of today’s fast flux networks, it’s worth revisiting their foundational tactics—those core variants that laid the groundwork for this ever-evolving threat landscape.

Three Essential Variants of Fast Flux Networks

- Single Flux: At its most basic, single flux involves tethering a single domain name to a constantly shifting pool of IP addresses. It’s like watching shadows dance—domains resolve to five, ten, or even more IPs per query, with DNS Time-To-Live (TTL) values often dipping below 600 seconds, sometimes plunging to just a few seconds during peak activity. This rapid churn ensures uninterrupted malicious operations, rendering traditional IP blocking almost laughably ineffective. By the time you’ve blocked one address, the network has already moved on.

- Double Flux: Building on this, double flux networks up the ante by not only rotating IP addresses but also frequently changing the authoritative name servers (NS records). Attackers randomly generate domains—think xkjd7fns9p.com—and pair them with fluxing IPs, layering anonymity and redundancy. The result? A dual shield that makes tracking or disrupting command-and-control (C2) infrastructure a Sisyphean task.

- Global IP Spread: Perhaps most insidious is the geographic chaos these networks sow. Their IPs are scattered across multiple countries and Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs), each managed by different entities. This global sprawl, powered by botnets of compromised systems, ensures defenders are always several steps behind, chasing a panther with a fish net.

Advanced Techniques in Fast Flux Networks

Today’s threat actors have layered even more complexity atop these basics. Fast flux networks now employ:

- Domain-Flux Networks: By leveraging DGAs, attackers can generate thousands of new domains daily, as seen in notorious botnets like Conficker. This ensures operational continuity even when defenders manage to take down some domains.

- Bulletproof Hosting Integration: The backbone of many fast flux operations, bulletproof hosting providers ignore takedown requests and law enforcement, offering criminals a resilient infrastructure for their campaigns.

- Traffic Evasion Techniques: Advanced actors employ traffic tunneling, encryption, and even legitimate services to cloak malicious communications, making detection a moving target.

- Dynamic DNS and Round-Robin DNS: These techniques allow networks to update DNS records on the fly and distribute traffic across a wide array of IP addresses, further bolstering their resilience.

- Use of Compromised Hosts: At the heart of fast flux is a vast, globally distributed army of compromised machines—often unwitting residential broadband users—acting as proxies and relays. This not only amplifies the network’s reach but also muddles attribution efforts.

Read More: Cyber Warfare 2025: Rising Global Threats And Essential Safeguards

Smart Ways to Defend Against Fast Flux Attacks

Fast flux attacks are relentless, but with a practical, layered approach, you can seriously raise your defenses. Here’s how to stay a step ahead:

Block and Sinkhole Malicious Domains

Don’t just block suspicious domains—redirect (sinkhole) that traffic to a controlled environment. This not only cuts off attackers but helps you spot compromised devices inside your network. Tools like EDR, UTM, and XDR can catch endpoints reaching out to these domains and isolate them fast.

Tap Into Threat Intelligence

Stay plugged into threat feeds and reputation services. Feed this intel into your firewalls and SIEMs so you can spot and block risky IPs before they become a problem. XDR can automate this, while EDR and EPS keep an eye on endpoints and block threats at the perimeter.

Watch for DNS Oddities

Deploy anomaly detection for DNS logs. Fast flux domains love to rotate IPs—sometimes every few minutes! XDR can flag endpoints making weird DNS requests, while EPS blocks anything known to be bad.

Check DNS TTLs and Geolocation

Keep an eye on DNS records with inconsistent geolocation or rapidly changing IPs. XDR helps spot these patterns, and EDR flags endpoints connecting to them.

Boost DNS Traffic Monitoring

Increase logging and monitoring of DNS activity. Set up alerts for new or ongoing fast flux patterns. XDR centralizes this data, while EDR and EPS catch suspicious behaviors in real time.

Team Up With ISPs and Registrars

Share what you find—malicious domains, IPs, patterns—with trusted partners and threat intel communities. XDR can automate takedown requests and block traffic from known bad actors.

Train Your Team

Phishing is often the entry point. Regular awareness training helps staff spot and report suspicious emails, especially those tied to fast flux campaigns.

Fortify Web Apps With NGFWs

Work with security pros to configure Web Application Firewalls that block fast flux traffic. XDR pulls in data from NGFWs, while EDR and EPS protect endpoints accessing risky web apps.

Adopt Zero Trust

Never assume trust—verify everything, always. A Zero Trust model, backed by strong access controls and continuous monitoring, keeps attackers at bay. XDR and EDR enforce these checks across your environment.

Back Up—And Store Safely

Keep regular, offline backups. If attackers strike, you can restore data without paying a ransom. EDR and XDR help spot ransomware activity early, and EPS blocks malware execution.

Use AI and Machine Learning

Leverage AI tools to analyze suspicious files and URLs for signs of fast flux. Many multi-layered UTM products isolate risky endpoints, XDR detects anomalies, and EPS blocks known threats.

Test Your Defenses

Regularly run red teaming and penetration tests with experts. These exercises reveal weak spots before attackers do, and your EDR/XDR/EPS solutions help you respond quickly.

Bottom Line: A Game of Cat and Mouse

Fast Flux isn’t just another item on a threat intel feed. It’s a blueprint — one that reflects the evolution of cybercrime from solo hackers to global, distributed enterprises. And as long as the infrastructure remains fluid, laws stay sluggish, and detection lags behind, the domain names may change, but the threat won’t.

If anything, it’s just getting started.